|

A Sculpture Collective, Rajaonā. |

According to the Records, Xuanzang went more than 40 Li southeast from the Kapotaka Monastery to Hinayāna Monastery (Rongxi 1996: 258). From the Hinayāna monastery, Xuanzang travelled more than 70 Li northeast to reach a big village south of the river Gaṅgā (Ganges). Conversely, the Biography of Xuanzang mentions him going without deviation from Kapotaka to Īraṇaparvata Country skipping the Hinayāna monastery and the village by the Gaṅgā in between the two (Beal 1914: 125-127).

The Hinayāna monastery was 8-13 km (40 Li, 1 Li = 323 mts) southeast of Kapotaka and had more than 50 monks. Xuanzang mentions a great stūpa in front of the monastery where the Buddha preached the Dharma to Brahmā and others for seven days. Beside it were ruins where the three past Buddhas sat and walked back and forth. Circumstantial evidence demonstrates that Barui (25° 09' 12'' N. 85° 54' 39'' E) is most likely the site of Kapotaka Monastery (Anand 2024). Eight to thirteen kilometres southeast of Barui leads us to several potential villages like Mahsaurā, Nadiyāwān, Bhamariyā, Bartārā, Imādnagar, Bakiyābād, Asthāwan and Benguchhā etc., that could represent the site of Hinayāna monastery mentioned by Xuanzang (refer to Fig. 2). Exploration of this long list of sites will be a long-drawn-out investigation. Therefore, I plan to defer this survey and take it up later.

From Hinayāna Monastery, Xuanzang travelled 70 Li northeast to a big village south of the Gaṅgā. The village was densely populated and the inhabitants were prosperous. Xuanzang noticed several beautifully adorned Brahmanical shrines in the Village. The Village in question should be 14-21 Km (70 Li) from the Hinayāna Monastery and situated south of the Gaṅgā (refer to Fig. 2). In my opinion, Rajaonā (25° 11' N. 86° 05' E) which is 13-20 km from the potential location of the Hinayāna Monastery (i.e., the group of villages Imādnagar, Bakiyābād etc.) and 18 km northeast of Barui, as the crow flies, is most likely the site of the prosperous village by the Gaṅgā. The ancient remains of Rajaonā correspond to the village described by Xuanzang.

I visited Rajaonā-Chouki (Rajaonā and Chouki are contiguous villages) on 31st July. Rajaonā-Chouki is 3 km, as the crow flies, northeast of Lakhisarai Railway station. It was the sacred month of Sāwan (July-August), and all roads in Lakhisarai led to the very popular Aśokadhām temple (25° 11' 37'' N. 86° 04' 34'' E). Aśokadhām is also known as Indradamaneśwar Mahādev shrine dedicated to Lord Shiva. At the helpdesk on the temple campus, I met Shri Jageswar Singh who evinced his interest in taking me for a heritage walk around the village (Rajaonā-Chouki). Jageswar Ji recounted how the Chouki mound, one of the prominent mounds in Chouki, was a playground for children when it lay fallow. On one such day in 1977, the children playing on the mound chanced upon the buried ancient Shiva Linga. The shrine was named after the 12-year-old Aśoka who had spotted the Linga. I met Shri Aśoka Ji, now in his late fifties, sitting inside the shrine's sanctum. I tried to interview Aśoka Ji but we could barely hear each other over the crowd's din. There is an eleven-member committee of villagers headed by the District Magistrate, Lakhisarai which manages the affairs of the Aśokadhām Shrine. The Aśokadhām complex is spread over four acres.

Aśokadhām is raised over the same Chouki mound that Alexander Cunningham partially excavated in 1873. The Chouki mound, which according to Cunningham was ‘large’ (Cunningham 1873: 154), is all but lost without a trace. Cunningham extracted two large pillars of blue stone from the mound. The pillars were 16 and a half inches square, ornamented with bas-reliefs. Some of the inscriptions on the pillars as per Cunningham were as old as the 7th or 8th century. Frederick Asher believes the maṇḍapa pillars retrieved from the Chouki mound currently kept in the Indian Museum, Kolkata are from the Gupta period i.e., 4th-6th CE (Asher 1986: 230).

Over the years the Chouki mound has revealed numerous artefacts. Countless artefacts exhumed from Rajaonā-Chouki have been stolen (lost to illegal trade), a few are removed to state museums and a fair few are now preserved in the Aśokadhām Temple museum. Nevertheless, many sculptures are kept in village collectives where they are worshipped. A documentation study of sculptural remains of Rajaonā-Chouki by Rupendra Kumar Chattopadhyay, KumKum Bandyopadhyay and Shubha Majumder identified thirteen sculptural ‘find-spots’ (i.e. clusters). The ‘find-spots’ include modern village shrines, private collections of villagers and sculpture collectives. They found more than a hundred sculptural remains in these ‘find-spots’ implying a strong Brahmanical (both Śaivāite and Vaiṣṇavāite) connection of Rajaonā-Chouki. The sculptures in Rajaonā-Chouki based on their stylistic grounds are tentatively dated between the 7th -13th CE (Bandyopadhyay, Chattopadhyay, Majumder 2015: 24).

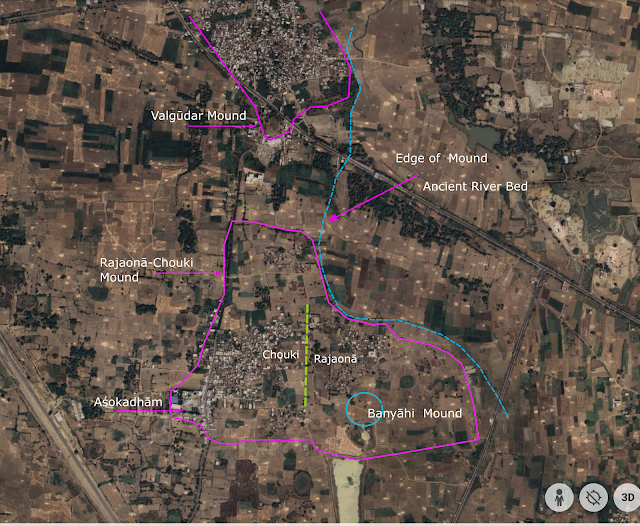

Jageswar Ji shared how his ancestors and the forefathers of other Bhumihār families who make up 60% of the inhabitants of Chouki migrated from Begusarai more than two centuries ago. They first settled in Valgūdar less than one kilometre north of Rajaonā. Later, they moved from Valgūdar and settled adjacent to Rajaonā around the early 19th century. The settlement was named Chouki because the Mauza (distinct parcel of land) where they settled was called Chouki. Rajaonā and Chouki are contiguous settlements with Rajaonā on the east and Chouki on the west. Valgūdar on the north of Rajaonā-Chouki is also settled on ancient remains (refer to Fig. 1). We can say that Valgūdar is contiguous to Rajaonā-Chouki. Still, unlike Rajaonā and Chouki which are settled on the same ancient mound, there is a gap of approximately 400 mts between the northern tip of Rajaonā-Chouki mound and the southern end of the Valgūdar mound.

|

Fig.1. Valgūdar, Rajaonā-Chouki and river bed of Gaṅgā |

|

| Aśokadhām Shrine. |

|

| Ancient Shiva Linga, Chouki Mound (Aśokadhām) |

|

| Sculpture collective, Aśokadhām |

|

| Shri Ashoka Ji |

|

| Sculptures kept in Aśokadhām Museum. |

|

| With Jageswar Singh Ji. |

|

| Banyāhi Mound |

|

| Banyāhi Tank |

|

| Broken image of Buddha, Mānjhi Tolā. |

|

| A sculpture collective, Rajaonā |

|

| Abandoned houses of Kayastha Families, Rajaonā |

|

| The steep and undulating shape of the northern face of the Rajaonā-Chouki mound. |

|

| Shikhar and Shivam, fields north of Rajaonā-Chouki. |

|

| New Lakhisarai Museum. |

|

| A neglected mound, Valgūdar |

Rajaonā-Chouki and Valgūdar are located in proximity to the confluence of the rivers Gaṅgā, Kiul and Haruhar making it an important trade centre in ancient times connecting Vārānasī, Pāṭaliputra, Tāmralipti and other trade centres along the Gaṅgā (refer to Fig. 3). There are many villages in proximity to Rajaonā-Chouki that have ancient mounds and sculptural remains. All these villages now fall under the modern city of Lakhisarai. An exploration led by Dr Anil Kumar identified more than 22 archaeological mounds spread over a 5 km radius of Lakhisarai Railway Station (refer to Fig. 3). Most of these mounds now have villages settled over them. Dr Anil has broadly clubbed them into three clusters making it a large settlement in ancient times. The first cluster consists of villages Valgūdar, Rajaonā-Chouki and Neri on the north and west of Lakhisarai Railway Station. The second cluster consists of villages Kiul, Kawai, and Jayanagar, south of the railway station and on the western bank of the river Kiul. The third cluster consists of the villages Garhi, Rāmpur northeast of Lakhisarai Station, Brindāban, and Ghosi Kunḍi southeast of the Railway Station. The villages of the third cluster are on the eastern bank of river Kiul (refer to Fig. 3). Cunningham believed the 4-mile long and 1.5-mile wide stretch of archaeological sites consisting of villages Rajaonā- Kiul-Kowaya-Jaynagar is part of an old city (Cunningham 1873: 153). Asher proposed that villages Rajaonā, Valgūdar and Jaynagar are contiguous and form an important urban centre (Asher 1986: 227).

D C Sircar in 1950 discovered three inscriptions on images reading Ādiṣṭhāna of Kṛimilā, meaning the City of Kṛimilā in Valgūdar (Sircar 1971: 248-255). Two of three inscriptions found in Valgūdar are from the reigns of Pāla kings Madanpāla (1143–1161 CE) and Devepāla (770-810 CE). A similar ‘Kṛimilā’ inscription on a stone slab from the reign of Śūrapāla (850–858 CE) was also found from Rajaonā. The inscriptions mentioning ‘Kṛimilā’ recovered from Munger and Nālandā refer to Kṛimilā as Viṣaya or district, which formed a part of the bhukti or province of Śrīnagara (present-day Patnā) (Sircar 1971: 248-255). Pali sources mention a town named Kimbilā (Kimmilā, Kimilā) where the Buddha delivered the Kimbilā Sutta (A.iii.247, etc.; S.iv.181f; v.322). Sircar is convinced that the Ādiṣṭhāna (administrative unit) of Kṛimilā, mentioned in the inscriptions is the same as the town of Kimbilā (Kimmilā, Kimilā) of Pali Buddhist sources (Sircar 1971: 248-255). Kimbilā as per Sircar is the Pali form of Sanskrit Kṛimilā (Sircar 1971: 248-255). Sircar believes that Valgūdar represents the ancient city or administrative unit of Kṛimilā district (Sircar 1971: 251).

Walking along the village streets and farm bunds we reached a projecting mound (25° 11' 34'' N. 86° 04' 52'' E) adjacent to a water body called Banyāhi Pokhara (refer to Fig. 1) The mound had a tractor ploughing it. There were exhumed brickbats all around. I was told almost all of the mounds in Rajaonā-Chouki including the Chouki mound are privately owned (raiyati). Jageshwar ji shared how until a couple of decades ago this mound adjacent to Banyāhi was two distinct mounds. The two mounds were levelled and merged for the convenience of cultivation. I noticed a small inscribed and broken image of Buddha lying under a tree. Another small image of Buddha was enshrined in a shrine by the mound. There was a settlement of the Mānjhi community north of the mound. These images of Buddha according to the Mānjhi people were unearthed from the mound. The dimension of the (Banyāhi) mound insinuates it to be a stūpa remains. Jageswar Ji then led me to a few more sculpture sheds, one in Kahār Tolā and another in Bhumihār Tolā (Durgā Sthān). Sculptures in these generations-old, community-led sculpture sheds were either exhumed in their locality or found by somebody from the respective communities. Jageshwar Ji recounted how Prof Anil Singh of Vishwa Bharti University played a key role in engaging the locals in safeguarding the artefacts kept in numerous sculpture sheds in and around Rajaonā-Chouki. His efforts to relocate the sculptures from these community-led sculpture sheds met uncompromising resistance. On the north side of the village, Jageswar Ji pointed towards a cluster of dilapidated houses. These fallen houses belonged to the Kayastha families. Kayastha people were the prominent landlords of Rajaonā when Bhumihārs arrived here some 200 years ago. Almost all Kayastha families have migrated from the village.

What surprised me was the expanse of the Rajaonā-Chouki mound. The mound is spread over a huge area. Rajaonā and Chouki villages are settled on a fraction of the mound. Based on the physical survey and studying it on Google Earth map, I estimate that the Rajaonā-Chouki mound could be spread over 200 acres. Over the years many mounds have been damaged. Most of the houses in Rajaonā-Chouki have reused bricks from these mounds. Many mounds in Rajaonā were vandalised to extract bricks to use as ballast for the railways (Cunningham 1873: 153). Jageswar Ji told me there were around 60 small and large ancient water bodies in Rajaonā-Chouki-Valgūdar. Most of the water bodies are now lost to encroachment.

The ‘prosperous village’ mentioned by Xuanzang was on the banks of Gaṅgā. Similarly, Kimbilā of the Pali sources was also situated by the Gaṅgā. If Rajaonā-Valgūdar (i.e. ancient Kṛimilā) represents the site of ancient Kimbilā and the prosperous village of Xuanzang it should be by the Gaṅgā. However, the main channel of the Gaṅgā presently flows 10 km north of Rajaonā-Valgūdar. As per Jageswar Ji, the Gaṅgā in ancient times flowed past Rajaonā (refer to Fig. 1) I met two young farmers, Shikhar Singh and Shivam who were busy irrigating paddy fields using jet pumps. According to Shikhar and Shivam, wellbore excavation in this stretch of land on the northeast of the village (Rajaonā-Chouki) reveals a thick bed of characteristic white sand of the Gaṅgā at a depth of around 12 ft. Presence of a thick layer of Gaṅgā sand below the surface is also reported in the brick kilns east of Valgūdar. This is a shred of conclusive evidence that the Gaṅgā in the past flowed past Rajaonā-Valgūdar. From the farmlands northeast of the mound, I could see that the mound appeared as if the ancient town/village was ensconced on the concave bank of the river (Gaṅgā). This is also evident from the steep and undulating shape of the northern face of the mound. The satellite imagery confirms that Rajaonā-Chouki-Valgūdar is situated on an ancient channel of the Gaṅgā. Almost every monsoon the Gaṅgā swells up to the edges of Rajaonā.

Kimbilā as per the Pali sources predates the historical Buddha, the Gautama (6th BCE). Kimbilā existed even at the time of the previous Buddha, the Kassapa (Pv.12; PvA.151). Regrettably, we don't have a chrono-cultural stratigraphy for Rajaonā-Chouki-Valgūdar. However, the antiquity of Kṛimilā/Kimbilā is confirmed by the presence of Northern Black Polished Ware (NBPW) in Rajaonā-Valgūdar (Chattopadhyay, Sanyal 2008: 263-264). Recent studies have established the dating of NBPW to as early as the 12th BCE (Tewari 2016: 6-8).

A survey of sculptural remains and inscriptions by the art historians in this region suggests extensive religious structural activities in Rajaonā-Chouki during the later Gupta (6th CE) and early mediaeval periods (Bandyopadhyay, Chattopadhyay, Majumder 2015: 24). F M Asher believes that the Brahminical shrine from the Gupta period in Rajaonā-Chouki was the lone shrine for many generations until the resurgence of activities in Rajaonā-Chouki and its surroundings in the 9th century (Asher 1986). Claudine Bautze-Picron observes that the early Hindu phase in the Lakhisarai area which was concentrated around Rajaonā-Chouki came to an end in the course of the 10th CE. There is no evidence of Buddhist art before the 11th CE in the Lakhisarai area (Bautze-Picron 1991-92: 242). But a Buddhist community must have extensively settled in the 11th CE in a relatively large area around the modern city of Lakhisarai as suggested by the presence of Buddhist images (and secondarily Hindu) dating 11th-13th CE in Jaynagar and Hassanpur, Kiul, Valgūdar, Ghosi Kunḍi (Bautze-Picron 1991-92: 239-241). Lakhisarai as per Bautze-Picron was a major Buddhist centre in the 11th-13th CE, as the Hindu images are very rare (Bautze-Picron 1991-92: 253).

Available evidence indicates that Rajaonā-Chouki-Valgūdar i.e., the city of Kṛimilā is Kimbilā of the Buddhist sources. Inscriptions suggest this place Kṛimilā was a flourishing religious-administrative unit from the Gupta period (4t-6th CE) to the Thirteenth CE (Kumar 2011: 29). Sculptural remains confirm that in the 5th-6th century, the Rajaonā-Chouki had Brahmanical shrines and was a flourishing religious-administrative unit. Rajaonā-Chouki also fits the distance and direction criteria mentioned by Xuanzang. We have ample data that confirms Rajaonā-Chouki is the big, prosperous village with several deva temples mentioned by Xuanzang.

With so many archaeological mounds in and around Rajaonā-Chouki, where is the stūpa to mark the presence of the Buddha mentioned by Xuanzang?

According to the Pali sources, Buddha during his stay in Kimbilā delivered the Kimbilā Sutta in a Veḷuvana (bamboo grove, A.iii.247, etc.; S.iv.181f; v.322). Xuanzang mentions a great stūpa to mark the place where the Buddha preached the Dharma for one night. The great stūpa as per Xuanzang was ‘not far to the southeast’ (Rongxi 1996: 258)/ ‘near the southeast side’ (Watters 2004: 196) of the Village. During his visits to villages and urban centres, the Buddha would stay in some grove or safe place some distance from the city/habitations. Veḷuvana, where the Buddha delivered Kimbilā Sutta is most likely the location of the great stūpa of Xuanzang.

Xuanzang has used the phrase ‘not far’/ ‘near’. Using my experience following the trails of Xuanzang, I can say that ‘not far’ or ‘near’ can sometimes extend up to 2 kilometres. Cunningham reported remains of an ancient stūpa in Brindāban on the other side of river Kiul (Cunningham 1873: 156). Brindāban stūpa mound (25° 09' 51'' N. 86° 06' 22'' E) is more than 4 km as the crow flies southeast of Rajaonā which I think is a little far to be the stūpa in question. Cunningham noted an image of Buddha and Bodhisattva Padmapāni near two mounds on the east of the Rajaonā (Cunningham 1882:14). Cunningham believed these mounds were remains of a monastery and stūpa. More than 150 years have passed since Cunningham visited Rajaonā. The sculptures he documented have been relocated. It is cumbersome to identify the exact mound mentioned by Cunningham. I trust the mound adjacent to Banyāhi Pokhara is the stūpa mound noted by Cunningham, and most likely the remains of the great stūpa mentioned by Xuanzang. Banyāhi Pokhara is on the southeast edge of the Rajaonā-Chouki mound i.e., on the southeast corner of the village (refer to Fig. 1). The great stūpa was also in the southeast of the Village. However, sans archaeological excavations, these are just an informed supposition.

Postscript

Sir Alexander Cunningham proposed the ancient remains of Rajaonā as the village of Lāvaṇīla (Cunningham 1873:153). Many of the identifications offered by Cunningham in this stretch of Xuanzang’s travel from Nālandā to Īraṇaparvata including that of Lāvaṇīla are implausible. It all began with the erroneous identification of Indraśailaguhā, which then had a cascade effect on the identifications of Kapotaka Monastery, Hinayāna Monastery, the village by the Gaṅgā and Lāvaṇīla, the subsequent sets of places following the Indraśailaguhā.

Cunningham identified Giddhdwāra, a cave at the southern face of Giriyak Hill (25° 01’ 28 N, 85° 30’ 51 E) as the Indraśailaguhā. The isolated hill of Indraśailaguhā as per Xuanzang was east of Nālandā Saṅghārama (monastery). However, Giriyak Hill is neither an isolated hill nor situated east of Nālandā. Giriyak Hill is the western edge of the 40 km long Rājgir range of Hill and is south of Nālandā. Even so, Cunningham was convinced that ‘Giriyak’, as etymologically is ‘Giri (mountain)’ and ‘ek (single)’, which he concluded is the same as Isolated Hill (Cunningham 1871: 16-20). From Indraśailaguhā Xuanzang next went to Kapotaka Monastery i.e., Pigeon Monastery. Pigeon Monastery was so named since a bird catcher inspired by the generosity of the Buddha became his follower. Cunningham identified the ancient remains of Tetrāwan as Kapotaka Monastery. Later, Cunningham reviewed his position and proposed the isolated hill of Pārwati as Kapotaka (Cunningham 1882: 6-7). Just as Giriyak according to Cunningham meant isolated hill, Tetrāwān (25° 07' 52'' N. 85° 35' 10'' E) and Pārwati (25° 05' 10'' N. 85° 39' 05'' E) according to him acquired the names from Tetar (partridge) and Pārāvata (pigeon) respectively (Cunningham 1873: 150-151).

|

Fig. 4. Identifications offered by Cunningham and the corrected identifications. |

|

| Indraśailaguhā, Pārwati Hill. |

Xuanzang on his way to Lāvaṇīla from Kapotaka touched a Hinayāna Monastery (40 Li SE of Kapotaka) and a big village by the Gaṅgā (70 Li, NE of Hinayāna Monastery). Cunningham proposed Apsaḍha two km as the crow flies southeast of Pārwati as the site of Hinayāna Monastery. Xuanzang’s next stopover from the Hinayāna Monastery was the big village by the Gaṅgā. But there was a situation. The path connecting the village by the Gaṅgā to Lāvaṇīla as per Xuanzang passed through ‘mountains’. Cunningham supposed the 12 km long Seikhpurā range of Hill east of Pārwati befitting the description of Xuanzang. To adjust the Sheikhpurā range of Hills between Kapotaka (Pārwati) and Lāvaṇīla, Cunningham had to find a site between Pārwati and the western end of the Sheikhpurā range to represent the ‘village by Gaṅgā’. Cunningham accordingly proposed the Matakhar Tāl (Matokhar Tāl, 25° 07' 47'' N. 85° 47' 13'' E) at the west edge of the Seikhpurā Range as the village by the Gaṅgā mentioned by Xuanzang (Cunningham 1873: 152). Matakhar Tāl lacked substantial archaeological remains and, most importantly, it is not by the Gaṅgā but more than 25 km south of the Gaṅgā. Lāvaṇīla as per Xuanzang was more than 100 Li (approximately 33 km) east of the village by the Gaṅgā. Cunningham accordingly proposed Rajaonā located 30 km as the crow flies east of Matakhar Tāl (village by the Gaṅgā) as the site of Lāvaṇīla (refer to Fig. 4).

P C Choudhary in 1936, based on the descriptions of Xuanzang proposed that Pārbati Hill may be the Indraśailaguhā (Chaudhari 1936: 302) and not Kapotaka Monastery as proposed by Cunningham. Pārbati Hill is now accepted as the site of Indraśailaguhā. Identification of Pārbati Hill as the Indraśailaguhā meant the sites after Indraśailaguhā would accordingly be displaced further east. The identification of Pārbati Hill as Indraśailaguhā invalidates the identification of all the subsequent sites following Indraśailaguhā like Matakhar Tāl (Village by the Gaṅgā) and Rajaonā (Lāvaṇīla) offered by Cunningham (refer to Fig. 4).

Cunningham was at the forefront of resurrecting the Buddhist geography following the accounts of Faxian and Xuanzang. Cunningham experienced a wide variety of handicaps including a lack of maps featuring archaeological details. Revenue and Topological survey maps available in the mid-19th CE were prepared by colonial rulers to facilitate taxation and to identify the vantage points for military purposes (Meenakshi 2023). Besides soliciting his assistants to survey, Cunningham relied on exploration reports by explorers before him. He would also inquire about the potential sites from the local officials. However, this was not enough as it is fair to assume that in the 19th century, awareness about antiquity was the last thing in the minds of local officials. Also, most of the archaeological sites in Bihar would be inaccessible as they were until the beginning of the 21st century. Regardless of the challenges Cunningham faced, he did exceptional work in delineating the basic map of the route taken by Xuanzang.

-Thanks to Shri Surinder Talwar for proofreading the story.

-Thanks to Dr Anil Kumar (Professor, Department of Ancient Indian History Culture & Archaeology, Santiniketan) for his guidance.

Bibliography:

Anand, D. (2024, August 22). Interpreting the travels of Xuanzang from Indraśailaguhā to Īraṇaparvata (Part I)- Kapotaka Monastery. [Blog post]. Available at:

https://nalanda-insatiableinoffering.blogspot.com/2024/08/interpreting-travels-of-xuanzang-from.html [Accessed 22nd August 2024]

Asher, Frederick M.; 1980, The Art of Eastern India, 300-800. Minneapolis: The University of Minnesota Press.

Asher, Frederick M.; 1986, Sculptures from Rajaonā, Valgūdar and Jaynagar: Evidence for an Urban Center. East and West, vol. 36, no. ⅓. pp. 227–46. JSTOR http://www.jstor.org/stable/29756765. Accessed 28 Mar. 2024.

Asher, F. M.; 2000, An Image at Lakhi Serai and Its Implications. Artibus Asiae, 59(3/4). pp.296–302. https://doi.org/10.2307/3249882 . Accessed 3 August. 2024.

Bandyopadhyay, K. K., Chattopadhyay, R. K., Majumder, S.; 2015, Recent Study of Sculptural and Architectural Remains from the South Bihar Plain: A Case Study of Rajaonā-Chouki Region. Journal of Bengal Art, Vol. 20. pp. 205–228.

Bautze-Picron, Claudine.; 1991-92, Lakhi Sarai, An Indian Site of Late Buddhist Iconography, and its Position within the Asian Buddhist World. Silk Road, Art and Archaeology. Kamakura: The Institute of Silk Road Studies, Vol. 2. pp. 240-284.

Beal, S.;1914, The life of Hiuen-Tsiang by Shaman Hwui Li by Kegan Paul. London: Trench Trubner and Co.

Beglar, J.D.; 1878, Report of a Tour Through the Bengal Provinces of Patna, Gaya, Mongir, and Bhagalpur; the Santal Parganas, Manbhum, Singhbhum, and Birbhum; Bankura, Raniganj, Bardwan, and Hughli; in 1872-73, Vol. VIII. Calcutta: Office of the Superintendent of Government Printing.

Buchanan-Hamilton, Francis.; 1925, Journal of Francis Buchanan Kept During the Survey of the Districts of Patna and Gaya in 1811-1812. Patna: Superintendent, Government Printing, Bihar and Orissa.

Chakrabarti, D. K.; 2001, Archaeological Geography of the Ganga Plain: The Lower and Middle Ganga. New Delhi: Permanent black.

Chattopadhyay, R. K., Sanyal, Rajat.; 2008, Contexts and Contents of Early Historic Sites in the South Bihar Plains: An Archaeological Perspective. Archaeology of Early Historic South Asia. New Delhi: Pragati Publications. pp. 247-80.

Cunningham, A.; 1871, Archaeological Survey of India, Four Reports Made During the Years 1862-63-64-65, Vol-I. Shimla: Government Central Press.

Cunningham, A.; 1873, Archaeological Survey of India, Report for the Year 1871-72, Vol. III. Calcutta: Office of the Superintendent of Government Printing.

Cunningham, A.; 1882, Archaeological Survey of India. Report of a tour in Bihar and Bengal in 1879-80, Vol. XV. Calcutta: Office of the Superintendent of Government Printing.

Jamuar, B.K.; 1977, Rajaona- An Archaeological Study. The Journal of The Bihar Purāvid Parishad, Vol I. Patna: Bihar Puravid Parishad.

Kumar, A.; 2009, Interesting Early Mediaeval Sculptures of Magadh: A Case Study of Sculptures from “Krimila Adhisthana.” Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, Vol-70. pp.1034–1048. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44147749. Accessed 25 July. 2024.

Kumar, A.; 2011, Kṛimilā: A Forgotten Ādiṣṭhāna of Early Medieval Eastern India. Indian Historical Review 38(1). Sage Publications. pp.23-50.

Meenakshi, C.S.; 2023, The history of geographical surveys in India during the British period. Indian Journal of History of Science 58. pp. 151–156. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43539-023-00088-y. Accessed 25 July. 2024.

Rongxi, Li.; 1996, The Great Tang Dynasty Record of the Western Regions. California: BDK America, Inc.

Sircar, D. C.; 1958, Three Inscriptions from Valgūdar. Epigraphica Indica-XXVIII. Calcutta: Government of India Press. pp. 137-145.

Sircar, D. C.; 1971, Studies in the geography of ancient and mediaeval India. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidas.

Tewari, R.; 2016, Excavation at Juafardih, District Nalanda. Indian Archaeology 2006-07- A Review. New Delhi: Archaeological Survey of India.

Watters, Thomas.; 2004, On Yuan Chwang’s Travels in India. Delhi: Low Price Publications.

Abbreviations of Bibliography:

Source of Pāli references: http://www.palikanon.com/english/pali_names/dic_idx.html

P.T.S. Means published by the Pāli Text Society.

SHB. Means published in the Simon Hewavitarne Bequest Series (Colombo).

A. Anguttara Nikaya, 5 vols. (P.T.S.).

S. Samyutta Nikaya, 5 vols. (P.T.S.).

Pv. Petavatthu (P.T.S.).

PvA. Petavatthu Commentary (P.T.S.).

2 comments:

Me personally very highly appreciate Deepak Anand Ji. Only Scholar knows who are you! Unparalleled work. I request to the Bharat Sarkar(central & local), this is the time Buddha related all holy place return to the world Buddhist peoples. We are dedicated mind to develop it all .Keep safe Buddhism must safe the world. Namo Triratnaya.khemeshbar453@gmail.com

Only world Scholars knows what's the value of the writings and the writer. Me personally highly appreciate to you and your associate. On the behalf of World Buddhist community I request local & central Bharat Sarkar leaders and highly officials, Buddha related all holy places transfer to us .We are dedicate mind to develop again.Namu Triratnaya khemeshbar453@gmail.com

Post a Comment