Walking in the footsteps of Bodhisattva Siddhārtha and Mahāprajāpatī Gautamī (Mahāpajāpatī Gotamī), following their renunciation trail, I arrived in Lumbīnī on the morning of the 24th July (2021). I started my foot journey from Tilaurākota (the Palace City), Kapilavastu at midnight on Āṣāḍha (Āṣhāla) full moon day, as the Bodhisattva Siddhārtha did more than 2600 years ago.

|

Sunrise at Anomā River (Ganḍak). Pic @Dharmraj |

In Lumbīnī, I stayed at Bodhi Institute Lumbīnī (BIL). BIL is a training cum practice center for novice monks and nuns established by monk-scholar Ven. Metteyya Sakyaputta. Ven Metteyya is also Vice Chairman of Lumbīnī Development Authority (LDA). Ven Metteyya is very passionately involved in the development and implementation of the master plans of Lumbīnī, Tilaurākot, and Rāmagrāma, the three important sites associated with the footsteps of the Buddha pilgrimage circuit in Nepal.

Please consider supporting the Retracing Bodhisattva Xuanzang Project

How your financial support are going to be utilised

The Government of Nepal is slowly but steadily making committed progress in the transformation of Lumbīnī, Rāmagrāma, and Tilaurākot into living heritage sites. I had extremely fruitful discussions with Ven Metteyya on the development of a walking pilgrimage trail connecting the two very significant Buddhist sites of ancient Kapilavastu, Piprāhwā in India and Tilaurākot in Nepal. Later in the afternoon, I visited Venerable Bhikkhu Maitri, Chief Thervāda monk, Nepal, in his monastery and sought his blessings.

I visited the Mayādevi temple in the evening. The Mayādevi Temple complex was open but the central shrine i.e. the Temple was closed because of COVID19. I spent my evening inside the complex with Dr. Bhola Gupta, who did his doctoral research in the history of the Lumbīnī Temple. He is also the personal assistant of Venerable Metteyya. I had always believed that Lumbīnī for a few centuries after the visit of local king Ripu Malla in 15th CE was lost into oblivion. Bhola ji informed me that contrary to this popular perception, the Lumbīnī Temple was never completely forgotten and it continued to be part of local worship tradition. The present name Rumindie is in fact R(L)umbini Dih evolved from the ancient name Lumbīnī. Dih means a ruined mound and the term is also used in Bihar. There was a shrine over the Lumbīnī mound when the site was discovered in 1890’s. Lack of patronage led this temple to become a ruin but it still continued to be worshiped by the local people and also continued to attract patronage from local landlords of the Choudhary family of village Khungai.

|

| With Ven. Metteyya Sakyaputta |

|

Traditional Nepali Thali. A generous lunch offered by my host, Bodhi Institute Lumbīnī. |

|

| With Ven. Bhikkhu Maitri |

|

Listening to Dr Bhola Gupta, The Mayādevi Temple complex. |

|

| The Mayādevi Temple complex, Lumbīnī. |

|

| Ripu Malla Inscriptions on the Ashokan Pillar, Lumbīnī. |

Shri Chandra Pathak, my walking partner to Rāmagrāma (a two day walk) joined me in the evening. The next morning, we started our journey at 3 AM. Our goal for the day was reaching Bhairahawā, 22kms from Lumbīnī. Immediately after daybreak it started getting warm. Our walking speed got affected due to the harsh sunlight falling directly on our faces. Just a few years ago the road connecting Bhairahawā and Lumbīnī was flanked with trees providing good shade to the travelers, which was now missing. Pathak ji told me how during his college years he would cycle 45 kms everyday to and from Lumbīnī to Bhairahawā in the shades of tree along the roads. The new highways being built these days are designed for heavy vehicular traffic and big trees flanking the highways can create obstructions during monsoons and windy weather.

In the evening I, along with Pathak ji, went to visit Nyahgayur Shanti Buddha Gumba. We were warmly welcomed by a small group of elderly women. They were aware of our foot journey and were expecting us in the morning. The shrine belonged to the local Gurung community (of Bhairahawā). Gurungs are traditional Buddhists following Mahāyāna lineage. The Gurung tribe originally belonged to higher Himalayas. All the women were lay practitioners living in the neighborhoods of the shrine. Evening is their usual communal time. I noticed a few of them were busy cleaning the shrine and some offering ritualistic prayers. They offered us traditional tea and bread. Elderly women, Shilang Maya Gurung, Gaja Maya Gurung, Radha Gurung and Nanda Gurung, were curious to know about my foot journey. They were very happy to learn that I was following the trail of the Buddha and Mahāprajāpatī. Shilang Maya Gurung mentioned that though they were born Buddhists, they knew very little about Buddhist history, almost ignorant. They knew Mahāprajāpatī as the foster mother of the Buddha but they knew nothing much about her great contributions. They, like people in India, are taught very little about Buddhist history through the prevailing education system. I saw the excitement on their faces when they learnt that I live in Bodhgayā. All of them since their younger days wished to make pilgrimage to holy sites associated with the Buddha in India. But, for this to happen they were first dependent on their fathers, then husbands and now their children. Pilgrimage could never happen because ‘We didn't feel like bothering them’, Gaja Maya Gurung said.

Patriarchy has not changed much since the times of Gautamī. When the Buddha first arrived at Kapilavastu, the Śākyan women were not initially allowed to attend the talks at Nigrodha monastery. It became possible only when Gautamī met King Suddhodana and took permission on their behalf. I can imagine similar resistance, both vocal and silent, from men folk when Śākyan women decided to renounce. We have to remember that they were housewives. It was an agrarian society. Traditionally women are the anchor, the foundation, the glue across generations holding the family together. These 500 women were now redefining their relationship to the family. They, for the first time, were acting on personal goals and interests that were threatening the established norms seen as weakening the family. Yet, the Śākyan women remained calm and resolved with their decision.

Finally, two years ago overpowered by the desire to pilgrimage once in their lifetime, the elderly and middle-aged Gurung women of Bhairahwā decided to make a pilgrimage to sacred sites in India by themselves. All women group! Unfortunately, just when the time arrived the COVID pandemic started. However, their plan is unchanged. They plan to do it once the COVID subsides. I thanked them for the wonderful conversation and wished to take them around the Mahābodhi Temple and other shrines in Bodhgayā, when they visit Bodhgayā.

|

Lumbīnī to Bhairahawā with my walking partner Shri Chandra Pathak. |

|

Nyahgayur Shanti Buddha Gumba, Bhairahawā. |

|

In a conversation with the Gurung Buddhist lay devotees, Bhairahawā. |

|

The historic Rohinī river. Pic@ Chandra Pathak |

|

| A wonderful morning walking in the drizzling rain...magical! |

|

| A tea break on the way to Rāmagrāma. |

|

| But first, let me take a selfie. Enroute to Rāmagrāma. |

|

| Simple cart route leading through lush green rice fields. Pic@ Chandra Pathak |

|

Standing in front of the Rāmagrāma Relic stūpa. Pic@ Chandra Pathak |

|

| Information board, Rāmagrāma Site. |

|

| With the local people at the Rāmagrāma Relic stūpa. |

|

| With Shri Rajdev, Ramdev and. Jitendra Kushwāhā, Khairahani. |

Next day we started for Rāmagrāma at 3am. It was still dark when we were crossing the historic Rohinī river, which formed the border between the Śākyan and Koliyān kingdoms at the time of the Buddha. The Buddha was a Śākya prince and his mothers Mahāmayā and Gautamī were from the royal family of the neighboring Koliyā tribe. Although the riverbed must be around 50mts wide, In the moonlight I could see a thin stream of water flowing there, something very unusual for the rainy season. However, it was somewhere here, on one of its banks that the Buddha in Jetthamasa (May-June), the hottest month of the year gave Attadanda sutta discourse (‘One Who Has Taken Up the Rod’) to resolve the water sharing between warring Śākyans and Koliyāns.

So much has happened in the last few decades in terms of water management, with dams and canals for irrigation, deforestation, receding himalayan glaciers, etc. that it is inconceivable how river Rohinī must have behaved in ancient times. Chandra told me that Rohinī is now mostly a rain-fed seasonal river. Siddhārtha (riding Kaṇṭhaka) may have either done river trekking to cross Rohinī in the darkness of night through an established place or may have used a bamboo bridge for commuting that may have existed over it. The team Gautamī on the other hand would have been heartedly and enthusiastically received on the banks of Rohinī by her maykā (parents home) siblings, the Koliyāns. The news of what was happening in Kapilavastu must have reached the Koliyāns.

With the daybreak it started drizzling, yet, we kept walking. Weather forecast for the week was occasional rain now and then. Fortunately, the drizzling stopped after some time. We arrived at Rāmagrāma Relic stūpa before noon. Rāmagrāma stūpa is one of the original eight stūpas, containing the body relics of the Buddha. Rāmagrāma stūpa was raised by the Koliyāns over their share of the body relics of the Buddha. According to the popular belief, two hundred years after the Mahāparinirvāṇa of the Buddha, Emperor Ashoka reopened seven of the original eight body relic stūpas, to redistribute the relics and create eighty-four thousand stūpas spread across the Indian subcontinent. According to Faxian and Xuanzang, Rāmagrāma stūpa was untouched by Ashoka. The Nāga King who lived by the stūpa requested the emperor not to remove the relics else he would be denied from worshiping the sacred relics.

Both the pilgrims shared the same story of how snakes living in the nearby pool and wild elephants took care of relic stūpa and routinely worshiped it. Faxian and Xuanzang have also mentioned about a śrāmaṇera (novice) monastery near relic stūpa to take care of the temporal affairs (of the stūpa). The Government of Nepal continues to respect the ancient tradition and has decided to not excavate the stūpa. Instead, a non-destructive geophysical survey of the site was done. The geophysical study has revealed it to be a brick stūpa from Mauryan period (3rd BCE) and embellished until the first half millennium CE. Scholars believe at the core i.e. inside the Mauryan brick cover is the earliest mud stūpa. A number of monasteries were built to the north and east of the stūpa and after the Mauryan period.

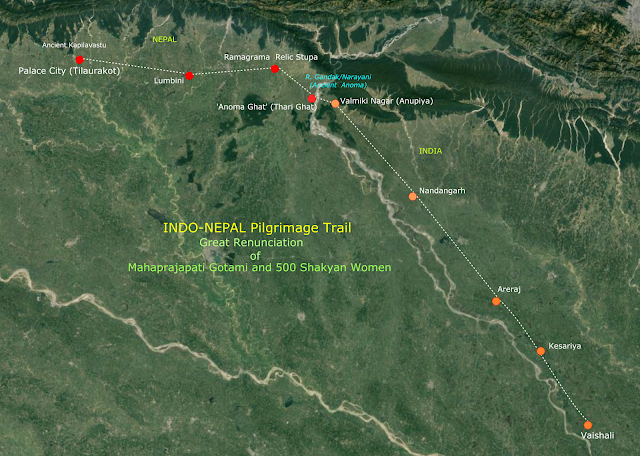

The relic stūpa site is a famed local attraction. Locally, the stūpa-mound is worshiped as Kotahi māi, a powerful deity, who cures devotees of ailments and punishes anyone who tries to rob bricks from this stūpa mound. I was keen on meeting elderly people here, who could describe to me the traditional cart route from Rāmagrāma to Daruābāri situated 30 kms south-east on the east side of river Ganḍak (ancient Anomā). All the community elders I met shared a route connecting villages Kusmā, Gobrahiyā, Sisaniyā, Majahuniā, Gopiganj/ Kushwā, Harpur, Barsare (Kolha river), Dhangarwā, Bargadwā, Barghate, Jagannathpur, Darkhase, Surujpura, reaching all the way to Thāri Ghāt on the western bank of Ganḍak. Thāri Ghāt according to them was the most favored place to cross river Ganḍak. They took a boat from Pakhliawān (Thāri Ghāt) reaching Bhaisālotan (Vālmikinagar) in India. Villagers also informed about some village Deurawā Siwān 1-2 kms east of Rāmagrāma stūpa that has mounds having ancient bricks similar in size to that of Rāmagrama stūpa but they were not aware of any village on this ‘ancient route’ connecting Rāmagrāma and Thāri Ghāt that had ancient mounds.

Rāmagrāma was situated on an ancient trade route connecting the Kingdoms of Kapilavastu and Koliyā with Anupiyā, Kushinagar and Vaiśālī. Team Gautamī may have camped somewhere here on the banks of the Jharahi river in some mango grove. A huge number of curious and anxious Koliyān visitors, old and young, siblings, nephews and nieces may have come to make last-ditch efforts to convince their near and dear ones to reconsider their renunciation decision. I can imagine the grueling situation of the matriarch, Gautamī, for a few she must be the reason behind the unwanted ‘rebellion’ but for the most, she must be the champion, an exemplar, a leader to emulate. I am sure with ample (dhyāna) practice she must have handled all of the emotions around very convincingly with grace. Properly equipped and provisioned for the journey, the group must have started early in the morning the following day for the next destination i.e. the river Anomā (the glorious). I think a few Koliyān sistren may have also joined them in their renunciation.

Shri Vinod Kushwāhā, an elected ward member of Ujjaini village situated near Rāmagrāma stūpa, welcomed us for the night stay in his house. People from Kushwāhā and its sister communities like Maurya, Saini, Śākya etc. in the states of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar are now becoming Buddhist’s enmasse. From my discussion with Shri Vinod ji, I realised that the Indian influence is now trickling down among the Kushwāhās in Nepal as well. Shri Vinod ji and his relatives are drawing towards Buddhism. He was very pleased that I was doing a foot journey to retrace the footsteps of the Buddha.

Next morning, Chandra and Vinod ji made a heart touching gesture by walking with me for a mile to see me off. After two days of walking with Chandra it was time to say goodbye to each other. I thanked Chandra for being a very understanding walking partner.

On my way to Thāri Ghāt, I briefly stopped for a meal at the workshop of Jitendra Kushwāhā in Khairahani village. Jitendra Kushwāhā is cousin of Vinod Kushwāhā ji. I initiated a conversation about the landscape, demography and behavior of the Ganḍak river with Shri Rajdev and Shri Ramdev Kushwāhā, father and uncle of Jitendra ji.

|

Somewhere on the trail to the Thāri Ghāt (Anomā Ghāt). |

|

| A bamboo bridge, Rampurwā. |

|

A patch of elephant grass and reed on the Ganḍak megafan, Narshai. |

|

| A patch of elephant grass and reed on the Ganḍak megafan, Narshai. |

|

| Site of the Anomā Ghāt shrine, Thāri Ghāt. |

|

| With Dharmraj at river Ganḍak. |

|

| Talking to the boatmen at the Thāri Ghāt. |

|

| The boatmen getting ready to sail me to the other side of the river Ganḍak (Anomā) to enter India. |

River Ganḍak originates from the higher Himalayas near Nepal-Tibet border (6000 mts). Rushing waters pass through deep canyons and steep georges of Himalayas for more than 500 kms and is joined by many tributaries on its way, before it spreads out into the Indo-Nepal flat Terai plains creating a large alluvial fan. The alluvial fan is approximately 10km in radius. For centuries Ganḍak has been creating havoc during monsoons. The Governments of India and Nepal in 1950’s onwards channelised many streams of Ganḍak into one and also created a barrage at Tribeni thus regulating the Ganḍak. As a result of these and many other flood controlling measures, other sister channels of Ganḍak dried up. These dried channels were subsequently transformed for cultivation. In the last 70 years more than 30 small and large villages/settlements have come up over this alluvial fan. Rajdev ji shared that his village Khairahani is now settled almost 9 kms from the present main stream of Ganḍak yet, these dead river beds get active in monsoons drowning his village and other villages settled on the Ganḍak megafan in the vicinity (see fig.1).

Xuanzang has mentioned this track from Rāmagrāma to the place where Siddhārtha sent back his horse Kaṇṭhaka ( i.e. the east bank of Ganḍak/Anomā) was through a ‘big forest’. This alluvial fan of sand, silt and gravel is ideal for grass and reed. I can picture the team Gautamī negotiating a 6-10ft wide, meandering cart road through tall, dense and luxuriant elephant grass forest. This 20 km long trail through the endless grass that you can’t see over, was devoid of any habitation at that time and there was also fear of wild animals appearing any moment from tall grasses. Many Śākyan women in the team Gautamī may have experienced an overwhelming sense of claustrophobia. The humid, dehydrating heat of the monsoon season may have added to their difficulties

Unlike the team Gautamī, I was privileged to walk on a blacktop road with people, villages and shopping complexes now and then. On my way I noticed patches of tall grasses and marshy fields here and there, giving a glimpse of the difficulties the team Gautamī may have experienced.

I was very warmly received by a small gathering of the Buddhist community at Narshai. The welcome was facilitated by my internet friend Dharmraj Sharma who too belongs to this village. Last year, while exploring this region on Google Earth I discovered contact details of Dharmraj. He works in network marketing. I have been in touch with Dharmraj since then. The gathering presumed me to be some Buddhist preacher. They were around thirty odd, young and old, mostly women. I shared with them about my foot journey project and that I was here to experience and explore the route taken by Bodhisattva Siddhārtha and Mahāprajāpatī Gautamī in their renunciation. They were not traditional Buddhists but were drawn towards the teachings of the Buddha because of Late Baba Saheb Ambedkar (1891-1956). Many of them were aware about the renunciation of Siddhārtha. Shri Vechu Gaud, a Parasai based scholar and journalist based on his research is of the view that Siddhārtha might have crossed Anomā (the glorious) at the present day Thāri Ghāt. The Buddhist community of Narshai under the guidance of Vechu Gaud are in fact now developing a shrine at Thāri Ghāt to commemorate the event of crossing of Anomā by Bodhisattva Siddhārtha. Anomā Ghāt shrine is situated 4kms south of village Narshai.

They invited me to take me to the ‘Anomā Ghāt’ shrine. I noticed that the shrine at the Thāri Ghāt is in its nascent stage. Here I met a few boatmen. According to them Thāri Ghāt is the oldest commuting point in this vicinity for people and bullock carts to cross the Ganḍak and to go to India.

It had rained heavily in the mountains the previous night making the river swell and look ferocious. Channelisation of Ganḍak river at Tribeni has shrunk the river bed at thari ghat. Presently it is 2-3kms wide but in ancient times it was 5-6kms wide. Hence before the channelisation, the rushing water from Himalayas would spread out on hitting the plains at Tribeni in many channels spreading out in a larger area making the river shallow and easy to cross. According to locals even now one can cross Ganḍak on foot during most of the time of year, except the rainy season.

From the Thāri Ghāt I noticed two mobile towers on the other side of the river. The twin mobile towers were situated 5kms east in Rāmpurwā village (Vālmikinagar, India). This meant Thāri Ghāt (in Nepal) on the west bank and villages Rāmpurwā and Daruābāri (both in India) on the east bank were in a straight line (see fig.1). Daruābāri has ancient ‘stūpa’ remains from 2nd CE. Xuanzang traveled 100Li (25-30 kms) East to reach the place where Bodhisattva Siddhārtha in his renunciation sent his horse Kaṇṭhaka and charioteer Chandaka back. Daruābāri is 30kms SE as the crow flies from Rāmagrāma. I have identified ancient ‘stūpa’ remains at Daruābāri with the three stūpas to mark events associated with the Great Renunciation mentioned by Faxian and Xuanzang.

In July 2020, on my foot journey RBX, I visited Shri Pramod Singh ji in village Rāmpurwā. He had informed me about the discovery of ancient bricks in large quantities on eastern bank of Ganḍak in between the Thāri Ghāt and the village Rāmpurwā. The boatmen at Thāri Ghāt confirmed this story told to me by Pramod Singh ji. They also saw those ancient bricks. The bricks were revealed because of heavy inundation that year (some 15-20 years ago) but got reburied under sand in the next few years. Pramod ji had also revealed to me the discovery of lots of potshards (potsherds) at some 3-4 ft depth from one of his fields on the track connecting Daruābari and Thāri Ghāt. These findings in between Thāri Ghāt and Daruābāri suggest there may have existed an ancient path connecting the two.

|

| Fig.1 Rāmagrāma to Daruābāri cart route trail through the Ganḍak megafan. |

|

| Map depicting my foot journey in Nepal. |

|

Map depicting Mahāprajāpatī Gautamī renunciation trail. |

So, Bodhisattva Siddhārtha in his renunciation, riding on his Kaṇṭhaka may have arrived at river Anomā early in morning, somewhere 1-2 kms further west of the present Thāri Ghāt. Possibly waited for the daybreak to happen. He most probably crossed the channels of the river Anomā sitting on his horse back. Kaṇṭhaka might have faced mostly knee or elbow deep water in sister channels and at a few places dipping till his shoulder and point of hip in the main channel of Anomā.

Things may not have been simple for the team Gautamī. Unlike Siddhārtha, they were on their feet. After an exhausting march approximately 25kms from Rāmagrāma through an isolated trail with no habitations and negotiating tall wild grasses and numerous channels of Anomā, they might have arrived in batches at the bank of the main channel of Anomā. They may have been totally exhausted unless it was a cloudy day in Āṣāḍha (also Āṣhāla, rainy month of July). A few batches may have even reached after sunset. Somewhere here at the banks of Anomā, their Koliyān siblings might have prepared the area clearing tall grass, leveling the field and spreading dry grass bed for their rest. Bonfires also may have been lit around the gathering to keep the wild animals away at night. Spreading their grass mats with their heads resting on pillows made out of their cloth bags, they must have contemplated their decisions to renunciate.

Women from ‘good and respected’ families don't step out of their homes. This is what I grew up hearing from my father, uncles, aunts, grandmother and grandfather and village elders. In my growing up days in my village, I never saw my mother and aunts stepping out of the confines of home to even shop. Sometimes when they did, it was under purdah / chaperone. However, much has changed in the present times but the situation faced by Śākyan women must have been as per the older tradition.

For many Śākyan women it was the first time coming out of their homes and out of their comfort zone and patriarchal control. This was a glimpse of their new life as nuns, to come soon. A few of them may have even contemplated ‘quitting’.

Sitting by the banks of Ganḍak at dusk absorbing the last few days of walking, experiencing and exploring the two great renunciations were so overwhelming. I gleaned every possible information from people I met during my 5 days of walking the great renunciation trail. I think I did fairly well in my exploration even if it is not the exact route taken by Siddhārtha and the team Gautamī. I am sure we are close. It was time to envisage the next course of action i.e. revival of the great renunciation trail. I am thankful to Shri Bikram Ji for giving me some hope of doing something tangible to revive the renunciation trail of team Gautamī.

Later in the evening, I was invited for dinner by a Buddhist family in Narshai. Narshai is situated on the western bank of Ganḍak separated by a 10kms long embankment running north to south.

I had sneaked into Nepal from the Aligarhwā border on 22nd July (2021) without proper permission. Reentering India through the integrated Indo-Nepal border check post could land me into some problems. Next day, early in the morning, I reached Ganḍak. The previous day I negotiated with boatmen to sail me to the other side of the river Ganḍak to enter India.

Team Gautamī may have had their breakfast before the day break. Koliyān siblings would have got the boats ready. Younger Koliyāns must be helping them embark and disembark the boats. 10-15 women in each boat. it must have taken them hours to get to the other side of Anomā.

I have goosebumps imagining the things these great nuns, to be, must have gone through.

Read my foot journey following Mahāprajāpatī Gautamī renunciation trail from Valmikinagar to Vaiśālī.

Story chronicled by Sheila Garrick and Surinder M Talwar.

Bibliography:

Allen, Charles (2008). The Buddha and Dr Führer: An Archaeological Scandal (1st ed.). London: Haus Publishing.

Anand, D. (2020, July 28). Piprāhwā to Tilaurakot: Celebrating the Ancient Kingdom of Kapilavastu. [Blog post]. Available from:http://nalanda-insatiableinoffering.blogspot.com/2020/07/piprahwa-to-tilaurakot-celebrating.html

[Accessed 21st August 2021]

Anand, D. (2017, June 20). Resolving the Puzzle of the ‘Palace City’ of Kapilavastu and Developing the ‘Kapilavastu Pilgrimage Trail’.[Blog post]. Available from:

http://nalanda-insatiableinoffering.blogspot.com/2017/06/resolving-puzzle-of-palace-city-of_20.html

[Accessed 21st August 2021]

Anand, D. (2020, August 8). New Discovery along Xuanzang's Trail-- Site where Bodhisattva Siddhārtha Cut His Hair. [Blog post]. Available from:

http://nalanda-insatiableinoffering.blogspot.com/2020/08/new-discovery-along-xuanzangs-trail.html

[Accessed 21st August 2021]

Bahadur, K.S.J.R.; 1988, Buddhist Archaeology in the Nepal Terai-II, Abhilekha, No.6: National Archive, Government of Nepal. https://www.spotlightnepal.com/2012/10/19/sylvain-l%C3%A9vis-le-n%C3%A9pal/

Beal, S.; 2005, Travels of Fah-hian and Sung-Yun, Buddhist Pilgrims from China to India, Low Price Publications, Delhi: originally published London: Trubner and Co.: 1869).

—— 1914, The life of Hiuen-Tsiang by Shaman Hwui Li by Kegan Paul. London: Trench Trubner and Co.

—— 1969, Si-yu-ki: Buddhist Records of the Western World, Translated from the Chinese Of Hiuen Tsiang, New Delhi: Oriental Books Reprint Corporation.

Coningham, R.A.E. and Acharya, K.P. and Manuel, M.J. and Davis, C.E. and Kunwar, R.B. and Simpson, I.A. and Strickland, K.M. and Smaghur, E. and Tremblay, J. and Lafortune-Bernard, A. (2018) 'Archaeological investigations at Tilaurākot-Kapilavastu, 2014-2016.', Ancient Nepal., 197-198. pp. 5-59.

Coningham, R.A.E. and Acharya, K.P and Strickland, K.M. and Davis, C.E. and Manuel, M.J and Simpson, I.A. and Gilliland, K. and Tremblay, J. and Kinnaird, T.C. and Sanderson, D.C.W (2013) 'The earliest Buddhist shrine: excavating the birthplace of the Buddha, Lumbīnī (Nepal)', Antiquity, 87 (338). 1104-1123.

Darnal, P; 2002, Archaeological Activities In Nepal Since 1893 A.D. To 2002 A.D, Ancient Nepal, Number 150.

http://himalaya.socanth.cam.ac.uk/collections/journals/ancientnepal/pdf/ancient_nepal_150_03.pdf

Führer, A.; 1897, Monograph on Buddha Śākyamuni’s Birth-Place in the Nepalese Terai, Archaeological Survey of Northern India, Vol. VI. Allahabad: The Government Press, N.W.P. and Oudh.

Misra, T. N, 1996, The Archaeological Activities In Lumbīnī, Ancient Nepal, Number 139.

http://himalaya.socanth.cam.ac.uk/collections/journals/ancientnepal/pdf/ancient_nepal_139_04.pdf

Rongxi, Li; 1996, The Great Tang Dynasty Record of the Western Regions, BDK America, Inc.

Jones, J.J. (trans.); 1956, The Mahāvastu Vol.III, London: Luzac & Co.

Garling, Wendy; 2021, The Woman Who Raised the Buddha: The Extraordinary Life of Mahāprajāpatī, Shambala Publications.

Watters, Thomas; 2004, On Yuan Chwang’s Travels in India, (Edited by T. W. Rhys Davids and S.W. Bushell), Reprinted in LPP 2004, Low Price Publications, Delhi. (First published by Royal Asiatic Society, London, 1904-05).

3 comments:

nice

Thanks for such an informative blog. Your effort is appreciable.

good to see this!!

chines resturant in sector 20

nearest chinese restaurant to me

indian foods restaurant near me

family restaurant in greater noida

food delivery resturant in Greater Noida

"Mohaprajapati Goutami" we pay always Vandana. Like this great renunciate Majesty Queen never find in human history. Her contribution knows no bound. Your tireless effort never in vain. One day will come, your dream must come true. Need only right determination and right effort. I believe you deserve it. I respect you and your helping colleagues. Triple Gem bless you.

Post a Comment