You can read this in detail:

Rāmpurwā- A compelling case for Kuśīnārā- I

Rāmpurwā a compelling case for Kuśinārā- Part II

Please consider supporting the Retracing Bodhisattva Xuanzang Project

How your financial support are going to be utilised

It is intriguing that if Rāmpurwā is Kushinagara - the site of the Great Demise of the Buddha - then where are the numerous shrines and stūpas which Xuanzang mentions were situated nearby and around the Ashokan pillar?

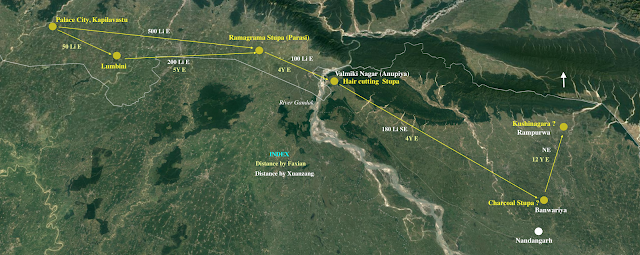

Besides the shrines related to the Great Demise and distribution of the relics of the Buddha, Xuanzang has also stated about the capital city of Kushinagara. The capital, according to Xuanzang, was 3-4 Li (1-2 kms approximately) south-east of the place of Mahāparinirvāṇa of the Buddha and south of the place where the Buddha was cremated. According to Faxian, the place of the Mahāparinirvāṇa was north of the capital city. This means one should look for the ‘capital city’ 1-2 km south of the Ashokan pillars i.e. around the villages of Bhitiharwā (27° 14' 15'' N. 84° 29' 15'' E), Pipariyā (27° 15' 41'' N. 84° 30' 36'' E) and Kahargaḍi (27° 15' 01'' N. 84° 29' 15'' E) (see map.2).

During my present visits to Rāmpurwā, I wanted to explore the villages and surroundings which qualify the descriptions by Xuanzang and Faxian of the capital city of Kushinagara. I first went to Bhitiharwā, which is known for its Gandhi Āshram where Mahatma Gandhi stayed during his visit in 1917. At Bhitiharwā, I met a local person named Shri Shatrudhan Prasad Chaurasia whose forefathers were among the team of people who facilitated Gandhi's stay there. The Gandhi Āshram is now a state protected monument. Shatrudhan ji turned out to be a history buff so I shared with him that the Ashokan pillars of Rāmpurwā could be marking the place of Mahāparinirvāṇa of the Buddha. He was very surprised and enthusiastically agreed to join me in exploring further.

Shatrudhanji recalled that during childhood, some 30 years ago, there used to be a ‘haunted’ mound located between the village of Pipariyā and River Panḍai. The mound was approximately 2 kms SE of the Ashokan pillars (see map.2.). I thought that the mound he was mentioning could be a potential spot for the capital city matching Xuanzang descriptions. We went to check out the mound but due to flooding, the mound was not approachable at the time. Hence we decided to find out about the mound from the people of Pipariyā. We met a person named Shri Nageshwar Rai at Pipariyā, in his mid 70’s, not keeping in good health but having a sharp memory. He vouched that there indeed was a mound believed by locals to be haunted. According to Nageshwar ji, the fields surrounding the mound upto 12 acres revealed ancient brick pieces and potshards every time they were deep ploughed.

Nageshwar ji informed me that he was not really a local in Bhitiharwā - his forefathers had come to Bhitiharwā as farm labourers. He said that actually no one in Pipariyā or the neighbouring villages of Rāmpurwā had lived there for more than four to five generations. The entire area was a dense forest extending into the foothills of the Himalayas in the north. Wild animals like tigers, leopards and bears stray out of the protected tiger reserve and enter the villages, especially during the monsoons. About 150 years ago, the British Indian government leased large chunks of land in this area to industrialists and businessmen for indigo cultivation. The businessmen who purchased these lands were rich and belonged to the cities so they never settled here.

Besides the forests teeming with wildlife, another actor that makes life in this region difficult is flooding. Each year during the months of monsoons i.e. July to September, the villages get severely flooded. Some of the elders who had gathered around me recollected memories of the flood in 2017 when the embankments and barriers constructed by the government to channelise the river water which had survived for decades were completely washed off. For one whole night, Pipariyā and Rāmpurwā villages were submerged under 3-5 ft of water. Water entered people’s houses. It was a dreadful night, they all said in one voice. However, the villagers are used to living with floods since it is an annual feature.

I could relate with what they were saying. The Ashokan pillars that were discovered at Rāmpurwā in the 20th century, weighing upto 40 tons each and approximately 50 ft high, were found almost flattened to the surface at the time of their discovery as revealed in the picture of the southern Ashokan pillar of Rāmpurwā taken during its excavation in 1907-08. It is as if they were brought down by some strong force, could be a powerful flood. This pic from 1907-08 excavation reveals that the brick platform over which the pillars were raised was also buried 7 ft under the present surface (i.e. neighbouring fields). This 7ft cross section at the pillar excavation revealed a layer of sand and earth which suggested that for centuries rivers flowed over this fallen Ashokan pillar (see pic.1).

|

Excavation of Ashokan Pillars from their findspot Rāmpurwā. @ASI |

|

| Ashokan Pillars were fallen and buried when discovered. Rāmpurwā. @ASI, 1907-08 |

|

Pic.1.Ashokan Pillars were buried under layers of sand and earth. Rāmpurwā.@ASI, 1907-08. |

Rāmpurwā is situated at the base of the foothills of Himalayas. During monsoon, rivers rush from the hills bringing abundant sand and silt submerging the whole area. While walking around Rāmpurwā, one can see numerous rivulets criss-crossing the landscape (see map.2.). The rivers also change their course frequently.

So here is my conjecture of what might have happened to the numerous shrines around the Ashokan pillars which Xuanzang mentions to be associated with the Great Demise: all the shrines around the two Ashokan pillars visited by Xuanzang got abandoned in the centuries around the end of 1st Millennia and might have collapsed or got washed away in severe floods. Further, as revealed in the excavation in 1907-08, a river was flowing over the pillar site for many centuries. Whatever remained of the shrines might have got submerged under layers of sand and earth. The discovery of brick fragments and potshards in the neighbouring fields is the most compelling evidence of all of this. Joginder Ji took me to a field 100 mts south west of the pillars, where a decade ago locals had discovered ancient antiquities while quarrying earth for making bricks at 5-6 ft below the surface. I spoke to a few people who were engaged in the nearby farms, all of them confirmed what Joginder ji had said. They suspect many of the fields around the pillars have ancient remains buried.

From the discussion with Nageshwar ji and fellow villagers of Pipariyā, I came to know that the twin pillars of Rāmpurwā have given birth to many folk stories. People called this place Gūlītāḍ. Gūlītāḍ is a corrupted name of the ancient rural sport of Gūllī-Ḍanḍā (Tip-cat according to Wikipedia). Locals believed that the giant people who lived here in ancient times used the two pillars as sticks to play Gūllī-Ḍanḍā. The mounds are still worshipped by locals as Bansati Mātā. The caretaker of the pillar site, Joginder ji had told me a story which he had heard from some visiting Buddhist pilgrims that after leaving Kapilavastu, the Buddha arrived at the site of the pillars with a friend and the two of them practiced meditation together for a few days. The two Ashokan pillars mark their respective spots of meditation.

I was told that that until just a few years ago, the Ashokan pillars were a haunted place in the jungle, but nowadays because of the occasional visits of foreign pilgrims, locals have become aware that the site is associated with a foreign religion (Buddhism). However, locals are indifferent to the site. From the little interaction I had with the locals, I realised that they have no plans for developing the site for its heritage value nor do they have a thought that the government should protect the site for showcasing it internationally. Basically, the locals do not realise at all that the site has the potential to be an attraction for international visitors.

|

Map.2. Bhitiharwā, Pipariyā and Kahargaḍi with respect to Ashokan pillars. |

|

| Myself with Shri Joginder Manhji at Ashokan Pillars |

|

Myself with Satrudhan ji, Nageshwar ji and others at Pipariyā |

|

Nageshwar ji, Pipariyā |

|

| Exploration with Satrudhan ji and Yadav Rai |

|

River Hargoḍā had eroded the field revealing brick-brats and potshards. |

|

| Exploration with Satrudhan ji. River Hargoḍā |

|

| Many agriculture fields in Rāmpurwā and around have ancient potshards. |

Nageshwar ji knew of a few more sections in the neighbouring agriculture fields which contained ancient potshards. He asked his son, Yadav Rai, to show it to me. Yadav Rai ji took me to the fields situated between the village of Kahargaḍī and River Hargoḍā. One could easily see that this piece of agricultural land was surrounded by River Hargoḍā on three sides and was much higher than the neighbouring fields. At many places the river had eroded the field revealing brick-brats and potshards at one cross section. The fields were covered with water and standing crops otherwise I was very keen to explore them. This ‘mound’ is about 50 acres wide and situated 2kms southwest of the Ashokan pillars. This perfectly matches Faxian and Xuanzang's description of the location of the capital city. According to Faxian and Xuanzang, the capital city was 10 Li (3kms approximately) in circuit located south of the place of cremation of the Buddha i.e. the spot where the second Ashokan pillar (northern pillar) was discovered at Rāmpurwā (see map.2).

From this visit and my previous visits to Rāmpurwā and its surroundings, I concluded that the shrines mentioned by Xuanzang related to the Great Demise and the capital city of Kushinagara should be buried somewhere between 6 to 8 ft below the surface. Using GPR (Ground Penetrating Radar) technology, it is very much possible to examine and map the remains of the shrines.

Revisiting the finds from Kasiā: Why Kasiā may not be Kushinagara

|

| 20ft nirvāṇa statue of the Buddha, Kasiā. @Wikimedia. |

I think it is important to examine and identify the site of Kushinagara correctly: whether it is Kasiā or Rāmpurwā. On the one hand, the distance and direction given by Faxian and Xuanzang of Kushinagara point to the twin Ashokan pillar site of Rāmpurwā. On the other, Kasiā contains strong evidence of association with the Buddha which is a 20 ft nirvāṇa statue of the Buddha. However, the nirvāṇa statute and other archaeological finds at Kasiā are inconclusive as has also been admitted by the excavators of the site who discovered it. Hence Kasiā cannot be proven as Kushinagara. Following is my analysis of the finds at Kasiā and why I believe Kasiā is not Kushinagara.

Between 1875-80, the most prominent mound in Kasiā which is near Gorakhpur known as the ‘māthā kunwar kā koṭ’ was excavated by British India official archeologist, A.C.L. Caralleyle. The excavations revealed three structures: (1) a large plinth inside the māthā kunwar kā koṭ, 150 ft (east to west) x 92 ft (north to south), which Caralleyle called the ‘Grand Plinth’ (Caralleyle 1885: 25-26); (2) remains of a temple (say Temple B1) on the western half of the ‘Grand Plinth’ which is now popularly known as the (Mahā)parinirvāṇa temple perhaps assuming it as the site where the Buddha attained Mahāparinirvāṇa and; (3) remains of a Stūpa (A) on the eastern half of the ‘Grand Plinth’ which is worshiped today as the nirvāṇa stūpa (See pic 2, 3).

1. The Mahāparinirvāṇa Buddha image excavated at Kasiā may not be the Mahāparinirvāṇa Buddha image described by Xuanzang

Carlleyle discovered a 20 ft long sandstone statue of Mahāparinirvāṇa Buddha in a ruined chamber inside Temple B1. The dimensions of the chamber were: 30ft 8in X 12ft (inside) and 47ft 8in x 32 ft (outside). The statue itself was severely damaged, several parts were missing. The statue was lying on a pedestal measuring 24ft x 5.5ft (Carlleyle 1883: 57-58). The inscription on the statue mentioned that it was donated by Haribala, master of the great vihāra in the 5th CE (Carlleyle 1879: 60).

This image of Mahāparinirvāṇa Buddha is from the 5th CE, much before the visit of Xuanzang which was in the 630's CE. This means that if Xuanzang visited Kasiā or if Kasiā is actually Kushinagara, Xuanzang must have seen this image.

The translators that I referred to - Samuel Beal (Beal 1969: II, 32), Thomas Watters (Watters 2004: II, 28) and Li Rongxi (Rongxi 1996:163) - all have mentioned that at Kushinagara there was a ‘large brick temple’ with ‘figure’/‘image or representation’/‘statue’ of the dying Buddha with his head in the north direction.

Neither of these translations have mentioned the Mahāparinirvāṇa image at Kushinagara to be made of stone. Xuanzang usually describes the make and dimension of images in the central shrines of the places that he visited. Generally, images of the Buddha and Buddhist deities in the principal shrines of Buddhist monasteries and temples used to be made of stucco. But in some places where other materials either stone or metal were used, Xuanzang has mentioned the material specifically like he did for Sankisa, Nālandā, Tilaḍhākā and Bodhgayā, to name a few. About the image of the Buddha descending from the Heaven in the ‘temple of descent’ at Sankissa, all three translators mention that it was a ‘stone image’(Watters 2004: 334) (Beal 1969: 203) (Rongxi 1996: 118) (Beal 1914:82). About the statue of Buddha in the central shrine of the Tilaḍhākā monastery, Xuanzang mentions it was 30 ft tall and ‘cast in brass’(Rongxi 1996:207)/ ‘metallic stone’ (Beal 1969: II, 103)/ ‘stone image’(Watters 2004: II, 105).

It is hard to believe that Xuanzang visited Kasiā and did not notice the 20 ft long stone image of Mahāparinirvāṇa Buddha dating from 5th CE. It can only mean that Xuanzang did not visit Kasiā - i.e. Kasiā is not the Kushinagara of Xuanzang. Xuanzang has not given details of the size and material of the Mahāparinirvāṇa Buddha at Kushinagara which can only mean that neither the image was large enough worth mentioning its size nor was it made of stone.

2. The first Mahāparinirvāṇa Temple at Kasiā was built only after 5th CE

The thickness of the wall of Temple B1 at the time of excavation was 10ft, and the exterior dimensions of Temple B1 were about 47ft 6in (north to south) x 32ft (east to west). Temple B1 had an ante-chamber and entrance to the west (Caralleyle 1885: 18). Vogel found remains of an earlier shrine (say Temple B2) beneath the Temple B1. Temple B1 was built over the remains of Temple B2. Temple B2 was much larger than Temple B1. Temple B2 had recessed corners and was presumably built in 7th-8th CE (Vogel 1908: 45-46) (see pic.2). On the north and south of the entrance of the Temples B1 and B2, Vogel found remains of deep niches alternating with pilasters of carved bricks. Remains of Temple B1 and Temple B2 overlapped the structure with niches based on which Vogel concluded that ‘structure with niches’ was built earlier than Temple B1 and B2. Vogel also noticed that the early structure with niches was not on the same axis as the Temples B1 and B2 (Vogel 1908: 47).

Excavation revealed that the niches of the early structure were filled up to extend the grand plinth to the present level. Vogel conjectured that the plinth was extended to build a temple (say Temple B3). Temple B3, according to Vogel, was created before the Temple B2 (the temple with recessed corner). Remains of stucco images of seated Buddha were found in the niches of the early structure. In one of the niches a votive inscription from 5th CE was found. Presence of inscription from 5th CE means the niches were not filled up until the 5th CE to extend the grand plinth which suggests Temple B3, if created on the extended plinth as conjectured by Vogel, happened only in or after 5th CE.

Vogel conjectured Temple B3 to be the first temple of Mahāparinirvāṇa. Temple B3, presumably rectangular in shape, was built, according to Vogel, to house the 20 ft sandstone image of Mahāparinirvāṇa Buddha offered by Monk Haribala in 5th CE (Vogel 1908: 48). This implies that there was no temple of Mahāparinirvāṇa Buddha at Kasiā (spot B) before 5th CE. It is highly improbable that the place where the Buddha attained Mahāparinirvāṇa would not have any temple till the end of 5th CE more so because images of Mahāparinirvāṇa Buddha were already in circulation from the 1-2nd CE which was 300 years before the first Mahāparinirvāṇa temple at Kasiā was built.

|

| Pic.2. General Plan Kasiā Excavation. @ASI, AR, 1906-07. |

|

Pic.3. ‘Grand Plinth’, Stūpa A, Temple B and central group of monuments.@ASI, AR,1904-05. |

|

Pic.4. Remains of ‘Temple B1’ and Stūpa A. @ASI, AR, 1904-05. |

|

‘nirvāṇa temple’ and ‘nirvāṇa stūpa' resting on ‘grand plinth’, Kasiā. @wikimedia |

3. ‘Grand Plinth’ at Kasiā not completely excavated yet

No further excavation was done to reveal the nature of the ‘structure with niches’ (i.e. early structure) and what lay even beneath the ‘structure with niches.’ Vogel presumed the ‘structure with niches’ to be a stūpa (Vogel 1990: 72) and on the basis of the style of the niches, ascribed the structure to be from the Kushāna period (1-2nd CE) (Vogel 1908: 34).

The excavation of the ‘grand plinth’ in Kasiā has been incomplete leaving few important questions unanswered: (a) What is the nature of the ‘structure with niches’? Is it a stūpa from the Kushāna period as proposed by Vogel or part of an early temple or another structure altogether?; (b) Where are the remains of the temple B3 created in 5th CE to house the 20ft Buddha image offered by Monk Haribala; and (c) When was the first temple built at spot B and how many times was it rebuilt?

To link Kasiā with Kushinagara we need to find the earliest temple built at spot B and for that we need a complete excavation of the ‘grand plinth’.

4. Nirvāṇa Stūpa (A) at Kasiā not the Ashokan Stūpa mentioned by Xuanzang

Xuanzang mentions the presence of a ruined Ashokan stūpa at Kushinagara, 200ft high, situated next to a temple containing an image of Mahāparinirvāṇa Buddha.

During the excavation of the ‘grand plinth’ in 1877-80, ACL Caralleyle discovered ‘remnant of the core of the dome of a great stūpa’(Caralleyle 1885: 17). This Stūpa (A) was situated 13ft east of Temple B1 and was shaped like a circular tower 14ft in height and 180ft in circumference. The circular tower was standing on a plinth 85 ft in length, 4ft 2in high. The plinth was resting on a second plinth 92ft in length and 4-5ft above the level of the older surface. Accumulated on top of this circular tower was a sloping pile of ruins 8-12 ft high. Above this pile of ruins, rose a high, rugged, pointed, perpendicular pile of bricks 23ft high (see pic.3.). That made the remains of the stūpa appear to be roughly 54-55ft higher than the surroundings (Carlleyle 1885: 25-26). Caralleyle’s speculation was that Stūpa A was the third stūpa built over the Ashokan stūpa mentioned by Xuanzang i.e. the stūpa by Emperor Ashoka in 3rd BCE lay underneath Stūpa A (Carlleyle 1883: 74-75).

In 1910, Hiranand Sastri excavated Stūpa A by sinking a shaft in the centre of the stūpa. At 14ft from the top, he discovered a copper vessel and a copper-plate which had Nidāna-Sūtra in Sanskrit crudely engraved and some portions written on it. The inscription also mentions that the copper vessel was given to the ‘nirvāṇa chaitya’ by Monk Haribala (Sastri 1914:65). Monk Haribala is the same name as of the monk who contributed the colossal 20ft Mahāparinirvāṇa statue of the Buddha at the end of 5th CE (Vogel 1908 :46). Sending the shaft further down, at the depth of 34 ft, Sastri discovered another stūpa 9ft 3in tall resting on natural soil. This stūpa had a small niche (1ft 9in high x 1ft 6.5in wide x 1ft 7.5in deep) which encased a well-modelled terracotta figure of Buddha, sitting cross-legged in meditation and facing west. Based on circumstantial evidence Sastri concluded the stūpa was built in the early 5th CE and was the first one to be made at this spot (Sastri 1914:65-66).

Excavation reveals that the earliest shrine at spot A is not an Ashokan stūpa (3rd BCE) as speculated by Caralleyle but a stūpa from 5th CE, 9ft 3in high - which is almost a thousand years after the time the Buddha attained Mahāparinirvāṇa in 5th BCE. So the 200ft Ashokan stūpa mentioned by Xuanzang remains to be found at Kasiā to link it with Kushinagara (mentioned by Xuanzang).

5. The Ashokan Pillar of Kushinagara still to be found at Kasiā

Xuanzang mentions an inscribed Ashokan pillar situated in front of the Ashokan stūpa at Kushinagara. Carrlleyle proposed a mound (C) situated on the east of the ‘grand plinth’ next to the Stūpa A as the site of the Ashokan pillar (Vogel 1908: 49) (see pic. 2) and searched hard for the pillar in the adjoining areas of the ‘grand plinth’ but did not find a trace of it. (Carlleyle 1883: 72; Carlleyle 1885:29). Vogel thought the pillar should be in front of the nirvāṇa Temple and dug a wide trench along the outer walls of the nirvāṇa temple but he too did not find any remains of a pillar (Vogel 1908: 51). The Ashokan pillar mentioned by Xuanzang which is crucial evidence to establish Kasiā as Kushinagaraa is still to be found.

6. Monasteries discovered at Kasiā not mentioned by Xuanzang

Xuanzang has not mentioned any monastery or monastic community as living at Kushinagara at the time of his visit. But excavation at Kasiā has revealed a three-storey monastery (D) right in front of the nirvāṇa Temple (B) (Vogel 1908: 35). This monastery was established in 5th CE and inhabited until 900 CE. So monastery D should have been functioning at the time of Xuanzang. Also, excavation in the south of monastery D has revealed remains of more monasteries (L, M, N, O) dating from the Kushāna period (1-2nd CE). Monasteries L, M, N, O were abandoned in the 5th CE so they must have been in ruins by the 7th CE when the visit of Xuanzang. The monasteries (L, M, N, O and D) could not have gone unnoticed by Xuanzang because they are spread across a large area only 15ft west of nirvāṇa Temple (B) (see pic.2). For other sites like Sankissa, Kapailavastu, Vaiśālī, Sārnātha, Nālandā, Mahābodhi, Xuanzang has not only mentioned the number and condition of the monasteries but also the number of monastics and the various traditions they were following. So it's highly improbable that Xuanzang had seen the monasteries and not recorded them. It can only mean that Kasiā was not visited by Xuanzang or Kasiā is not the Kushinagara of Xuanzang.

7. The Two Boundary Walls of Kasiā not mentioned by Xuanzang

Caralleyle and Vogel both saw remains of a wall bordering three sides of the ‘grand plinth’ and its immediate surroundings (māthā kunwar kā koṭ) and another 5000 ft long wall enclosing ‘the outer or monastic city of Kushinagara’(Vogel 1990: 58,74). The outer boundary had one gate on the southern side. Vogel could not find anything to help him in ascertaining the age of the boundary wall but taking into account the dimensions of the bricks used in the wall which were 13.5in x 7.5in x 2.5in and 14in x 8in x 2in, Vogel concluded the wall was contemporary to the early plinth and early L-M monastery i.e. belonging to the Kushāna period (1-2CE) (Vogel 1990: 74).

These boundary walls must have existed at the time of Xuanzang but he has not mentioned them. This is unlike Xuanzang - if the walls existed at the time of his visit, he would have mentioned the walled shrines and campuses as he did for Sankissa, Nālandā, Mahābodhi.

8. No monuments at Kasiā from the period of Buddha’s Mahāparinirvāṇa (5th BCE)

Excavations in three phases (1875-80, 1904-07 and 1910-12) revealed that Temple B and Stūpa A on the ‘grand plinth’ surrounded by shrines around them comprised the central group of monuments of Kasiā. The ‘grand plinth’ was never completely excavated to reveal the earliest monuments inside it. Vogel who made some excavations of the ‘grand plinth’ based on circumstantial evidence proposed that at an early date there must have existed on site B the first i.e. the ‘earliest’ shrine (at Kasiā), presumably a stūpa. Probably in the Kushāna period (1st-2nd CE) a second structure was built over the first structure. The second structure had niches from the Kushāna period (1st-2nd CE) that were excavated by Vogel. It was found that the ‘structure with niches’ had engaged under its projecting part many small stūpas on east, south and west (see pic 2, 3). This meant these stūpas on the three sides of the ‘grand plinth’ predate the ‘structure with niches’ i.e. they were built before the 1st CE. Vogel proposed that these stūpas encircling the ‘grand plinth’ on three sides were erected around the ‘earliest’ structure buried inside the ‘grand plinth’.

Beside that there were remains of small monasteries Q-Q’ from Gupta period (4-5th CE) and W and U from ‘Mauryan’ period (2nd-3rd BCE) on the north side of the ‘grand plinth.’ There was another structure H from ‘Mauryan’ Period engaged with the ‘grand plinth on NE corner. All these monuments were found to be oriented as if pointing towards/erected a some central shrine i.e. the earliest structure at spot B. (Vogel 1908: 46-49).

Vogel even admitted in his report ‘...these conclusions will have to be considered as tentative. A further examination of the plinth may either confirm or modify them’(Vogel 1908: 49). So the existence of an ‘early shrine’ inside the ‘grand plinth’ is still just Vogel’s guesswork from 1904-05. Further excavation of the ‘grand plinth’ has not happened after Vogel. If Kasiā is indeed the place of Mahāparinirvāṇa of the Buddha, it would have structures and antiquities from 5th BCE which have not been established by the excavations at Kasiā so far.

9. Seal-Dies and Sealings found at Kasiā suggests the site to be Vishṇudvīpa

Numerous terracotta seals dating from 400-1000CE belonging to monastery of Great Decease (Śrī Mahāparinirvāṇa vihāre bhiksu- saṅghasya) were discovered from excavations at Kasiā. Barring a few, most of the seals have distinct marks of strings on the reverse side which indicates these seals of the convent of Great Decease must have been glued to documents and letters (Vogel 1990: 82). However, it cannot be ascertained whether these seals were issued by the monastery of Kasiā or received by them from other monasteries.

Majority of these seals were discovered from the refuse heap which suggests these seals had been discarded after use, and many of the seals were broken which means they were attached to parcels which had arrived from outside (vogel 1909: 58). These evidence suggest the seals of the convent of Great Decease were not issued but received at the Kasiā monastery. Another evidence that Kasiā monastery was not issuing the seals is that not a single seal-die (i.e. cast) of Mahāparinirvāṇa vihāre has been discovered in excavations at Kasiā.

A major find from Kasiā that can shed light on its actual significance is one seal-die (cast/mould) reading Śrī Vishṇudvīpa vihāre bhikshu saṅghasya (of the community of friars at the Convent of Holy Vishṇudvīpa) and three seal-dies reading Aryāsṭa-vṛiddhai (for the growth of the noble eight). The discovery of these seal-dies means they were used to issue the respective seals at the convent of Kasiā. Vogel writes that the town of Vishṇudvīpa (Vethadīpa) was one of the eight recipients of the body relics of the Buddha. According to Buddhist literature, people of Vishṇudvīpa constructed a stūpa over the body relics of the Buddha. The discovery of seal-die of convent of Vishṇudvīpa at Kasiā led Vogel to propose that Kasiā could be the site of one of the eight great stūpas built over the body relics of the Buddha and as Vishṇudvīpa was intimately connected with the tradition of Buddha’s death, we can assume that between the two convents there existed a close relationship necessitating a continual exchange of documents. This could also explain as to why only one type of seals - of the convent of Mahāparinirvāṇa - were found at Kasiā. The monastery of Kasiā was affiliated to the larger monastery of the Great Decease and the bulk of correspondence happened with that monastery (Vogel 1909: 61).

The discovery of three pieces of seal-dies bearing ‘for the growth of the noble eight’ (Aryāsṭa-vṛiddhai) but no evidence of impressions produced from them among the numerous clay sealings and tablets found led Vogel to infer that the tablets produced with these seal-dies were given to pilgrims who visited the site. A similar die was found at Pakhnā Vihāra near Sankisa (Vogel 1909: 60). Vogel proposed that ‘the noble eight’ mentioned in the inscription referred to the eight principal places of Buddhist pilgrimage. But I think the inscription could be referring to the original eight great stūpas built over the body relics of the Buddha - Vishṇudvīpa being one of them.

The discovery of seals and seal-dies suggests that Kasiā was probably the recipient of the seals of the convent of Great Decease and may be issuing seals of the convent of Holy Vishṇudvīpa. Hence, Kasiā is most likely the ancient Vishṇudvīpa, not Kushinagara.

10. Excavators of Kasiā did not confirm it as Kushinagara

Indologist and historian Vincent Arthur Smith (1843-1920) was not convinced that Kasiā was Kushinagara because it’s distance and direction was not in consonance with those mentioned by Xuanzang. Agreeing with Vincent Smith, the Director General of Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), John Marshall, initiated excavation at Kasiā in 1904-05. Marshall wanted to find conclusive evidence to establish Kasiā as Kushinagara (Vogel 1908: 33-34).

In his excavations at Kasiā from 1904 to 1907 spanning three seasons, Vogel discovered numerous seals of Mahāparinirvāṇa monastery. He believed these could not be taken as conclusive evidence for Kasiā to be the final resting place of the Buddha (Vogel 1990:83). Vogel also discovered the seal-die of Convent of Holy Vishṇudvīpa based on which, he mooted the idea that Kasiā could be Vishṇudvīpa - one of the eight places that had received body relics of the Buddha (Vogel 1909: 34-35).

Hiranand Sastri, who conducted the last excavation at Kasiā in 1911-12, discovered a copper plate from Stūpa A inscribed with nirvāṇa cetiya. Sastri thought this inscription was not conclusive evidence and wrote in his report: “no such document was brought to light which could finally settle the identity of Kasiā” (Sastri 1915: 134). Sastri had also conducted excavations in Rāmābhāra to identify it with Mukuta-bandhana, the place where the Buddha got cremated, but was not convinced with that identification as well. Sastri was the last official of the ASI to excavate Kasiā and strongly recommended more explorations at both Kasiā and Rāmābhāra to identify them with places associated with the Mahāparinirvāṇa of the Buddha. He wrote in his report: “the topographical problem still requires an indisputable solution for which further exploration seems desirable” (Sastri 1915 : 135).

Thus we see that no fresh excavation or study was initiated by ASI after 1912 to identify and resolve the conundrum. Archeological evidence available from Kasiā so far cannot establish it as Kushinagara.

|

| Gratitude to the Gandhi Ashram, Bhitiharwā. |

Story chronicled by Dr. Aparajita Goswami

Bibliography:

Beal, S.; 2005, Travels of Fah-hian and Sung-Yun, Buddhist Pilgrims from China to India, New Delhi: Low Price.

—— 1914, The life of Hiuen-Tsiang by Shaman Hwui Li by Kegan Paul. London: Trench Trubner and Co.

—— 1969, Si-yu-ki: Buddhist Records of the Western World, Translated from the Chinese Of Hiuen Tsiang, New Delhi: Oriental Books Reprint Corporation.

Carlleyle, A.C. L.; 1883, Archaeological Survey of India Report for the Year 1875-76 and 1876-77, Vol XVIII Published by ASI, GOI, 2000, (First Published in1883).

Carlleyle, A.C. L.; 1885, Archaeological Survey of India Report for the Year 1877-78-79 and 80, Vol XXII, Published by ASI, GOI, 2000, (First Published in1885).

Laidlay, J. W.; 1848, The pilgrimage of Fa Hian: from the French ed. of the Foe koue ki of MM. Remusat, Klaproth, and Landresse; with additional notes and illustrations.Calcutta: J. Thomas, Baptist Mission Press.

Rongxi, Li; 1996, The Great Tang Dynasty Record of the Western Regions, BDK America, Inc.

Vogel, J. Ph.; 1908, Archaeological Survey of India, Annual Report-1904-05, Superintendent Government Printing, Calcutta.

Vogel, J. Ph.; 1990, Archaeological Survey of India, Annual Report-1905-06, Published by Swati Publication, Ashok Vihar, Delhi.

Vogel, J. Ph.; 1909, Archaeological Survey of India, Annual Report-1906-07, Superintendent Government Printing, Calcutta.

Sastri, Hiranand.; 1914, Archaeological Survey of India, Annual Report-1910-11, Superintendent Government Printing, Calcutta.

Sastri, Hiranand.; 1915, Archaeological Survey of India, Annual Report-1911-12,, Superintendent Government Printing, Calcutta.

Watters, Thomas.; 2004, On Yuan Chwang’s Travels in India. Edited by T. W. Rhys Davids and S.W. Bushell. New Delhi: Low Price.

Anand, D. (2015, March 7). Rāmpurwā a compelling case for Kuśinārā- Part II. [Blog post]. Available from:

http://nalanda-insatiableinoffering.blogspot.com/2015/03/Rāmpurwā-compelling-case-of-kusnara-ii.html

[Accessed 18th September 2020]

Anand, D. (2013, March 1). Rāmpurwā a compelling case for Kuśinārā- Part I. [Blog post]. Available from:

http://nalanda-insatiableinoffering.blogspot.com/2013/03/Rāmpurwā-compelling-case-for-kusinara.html

[Accessed 18th September 2020]

Anand, D. (2015, March 11). Of Kites, Bribes and Relics. [Blog post]. Available from:

http://nalanda-onthemove.blogspot.com/2015/03/of-kites-bribes-and-relics.html

[Accessed 18th September 2020]

Goswami, A., Anand, D.; 2016, The Pilgrimage Legacy of Xuanzang, Nalanda: Nava Nalanda Mahavihara (Deemed University).

5 comments:

very interesting post. I think most sites have problems with identification other than lumbini where the inscription on the pillar positively identifies it as such.

Thank you Deepak ji, fascinating as always! Much appreciate your efforts. Very interesting.

incredible exploration of ancient values

Thank you so much for listing a unique content!

Get Professional high quality of Voice Recorder in Anand Vihar at an affordable price with cash on delivery is available. We are listing all kinds of Spy Hidden Gadgets for Home Security. If you have any issues please contact our well-educated experienced experts at 9999332099/2499.

Thanks a lot for sharing!

Looking for a Mini Spy Camera in Anand Vihar New Delhi? Visit Spy World for top-quality surveillance devices. Keep an eye on your surroundings discreetly and effectively with our range of spy cameras today! For any query: Call us at 8800809593 | 8585977908.

Post a Comment